Of the many brutal scars that Partition left on South Asia, perhaps none is as raw as the India-Bangladesh border today. In the wake of an anti-establishment revolution, Bangladeshi Hindus have seen brutal persecution and varying degrees of support and solidarity. Before and after 1947, Bengal saw many bouts of religious violence. But in many ways, these were the results of 20th-century nationalism, rather than the astonishing history of Islam in Bengal. Though Islam first arrived with Turkic looters and conquerors, it only became the majority religion of eastern Bengal through the grandest, slowest force of Indian history—the flow of the Ganga River.

From Sword to pen

In 1236 CE, the Tibetan pilgrim Dharmasvamin trekked down from the ice-clad Himalayas to balmy Bengal. Graduates from Bengal had helped spread Buddhism among Tibet’s clans, just when the region was emerging from political anarchy into a stable, monastery-dominated landed order. But there were rumours of catastrophe.

Arriving in Bengal, Dharmasvamin, to his horror, found that there had indeed been a disaster, and experienced its aftershocks first-hand. While crossing a river, he found himself sharing the boat with two Turk warriors. They asked Dharmasvamin to hand over his gold, but he indignantly refused and said he would complain to the local Raja. Furious, the Turks snatched his begging bowl and threatened to kill him. Other Buddhist pilgrims intervened and convinced Dharmasvamin to pay up to save his life.

Dharmasvamin’s experience wasn’t uncommon in 13th-century Bengal. After the consolidation of the Delhi Sultanate in the early 1200s, bands of young Turk warriors had ventured down the Gangetic Plains seeking plunder. Their fast-moving cavalry easily outmanoeuvred the ponderous infantry armies of Bengali rulers. They looted and burned Buddhist monasteries rich with centuries of donations and seized control of cities. Soon, the Turks became a tiny and conspicuously Muslim ruling class within a vast countryside.

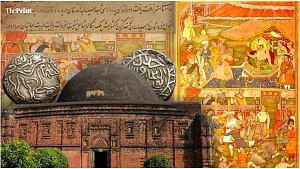

These early Muslim rulers of Bengal, as historian Richard Eaton writes in The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier 1204–1760, did not bother to adopt the culture of their subjects. Instead, their language and architecture looked toward distant Muslim power centres in Baghdad, Iran, and Delhi, leaving the countryside to be ruled by Hindu Kayasthas and the descendants of older Hindu and Buddhist lords. Over the next hundred years, Iranian and Central Asian Sufis—and their Indian disciples—spread through Bengal, converting frontier peoples, translating Sanskrit texts, and insisting on the legitimacy of Islamic kingship. Their support was desperately needed: as an isolated class of foreign rulers, the Bengal Sultans were always vulnerable to courtly intrigues and coups.

Such a coup was conducted by Hindu landlords in the early 1400s. One of their sons was placed on the throne of Bengal. In a compromise with urban Muslim warriors, the boy converted to Islam and was placed under Sufi tutelage. When he became Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad (r. 1418–1433), he reoriented the Bengal Sultanate from its obsession with distant Iran, toward Bengal’s own rich culture. He patronised Brahmins, issued coins with motifs of the goddess Durga’s lion, and constructed mosques in Bengal’s traditional brick architecture. The Bengal Sultanate, rejuvenated, fended off an invasion from the neighbouring Jaunpur Sultanate and expanded toward Tripura and Odisha. But its subjects, like those of other Sultanates, remained primarily Hindu. Yet great geopolitical changes were on the horizon.